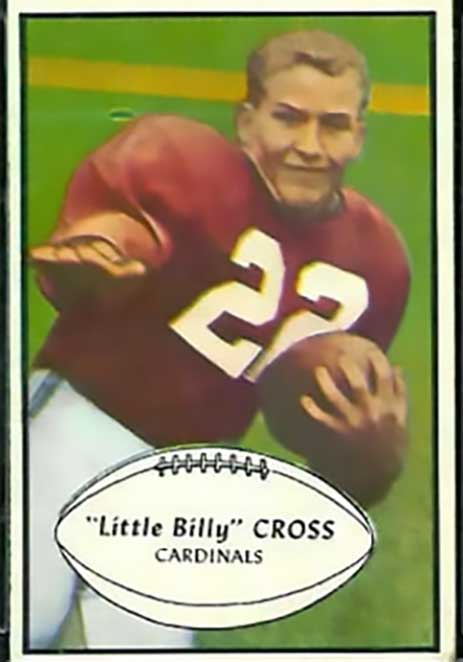

Bill Cross

There have been quite a few beefy linemen who have been nicknamed "Tiny" (Cahoon, Engebretsen, Nicholes, Nordstrom, etc.), but how many really tiny players have found a place on pro rosters?

That question was posed to me by Billy J. Cross, the mighty-mite, pint-sized 5-foot-6, 150-pound halfback with the Chicago Cardinals in the early 1950s. Pat Summerall, his old roommate1 had mentioned on a television broadcast that Cross was the smallest player to ever play pro football. The diminutive Cross, now retired in his hometown, asked me if I could verify Summerall's assertion. In taking a quick survey of references in my library, I was able to inform him that he very probably was the smallest player in the modern post-1950 era.

Billy Cross had a respectable 3-year career in the NFL He was more than just a spot player, even though he did return punts and kickoffs and performed other duties now delegated to special teams. The clippings preserved in his scrapbook are proof positive that this tiny terror from the Texas Panhandle was skilled at blocking, defense, running, pass receiving, kicking and quarterback on occasion.

He first reported to the Cardinals training camp in Lake Forest, Illinois in 1951. He had been picked as a late draft choice at the annual winter meeting when all the teams were just shooting in the dark. Not much was known about him and presumably not much was expected. From out of little West Texas State College, Cross had never seen a pro player in his life. He recalled, "I felt like I had knocked on the wrong door." It wasn't that he didn't think he could make the team -- Billy had confidence oozing out his pores -- but he just felt like everyone there, from the coaches to the 80 to 100 players trying to make the team were saying, "What is that little boy doing here?"

A story even made the papers about the first time Mrs. Violet Bidwell Wolfner, the owner of the Cardinals, saw little Billy He was strolling across the training camp lawn with Gene Ackerman, a 6-foot-5 end prospect from Missouri. "Who's son is that with Ackerman?" asked Mrs. Wolfner.

All of this judgmental adversity was deja vu all over again for Cross. It brought back memories of when he was a senior in Canadian High School, "I wanted to go to TCU. Dutch Meyer was coaching there at that time. I met him at the state track meet. He looked at me and said, 'Son, you are too small for college.' I was afraid that would happen in pro ball and I wouldn't ever get the chance."

Later in life, Billy coached with Bum Phillips at UTEP. When Phillips sent Cross out on a recruiting trip he would always remind him, “Don't bring back anyone you can look eye to eye with."

Cross came to the attention of the coaches during that first week in training camp in an intra-squad game. Leo Sanford recalled, “Bill and I came to the Cardinals as rookies. He was scared to death that first week and then the first time they let him run with the ball he ran crazy. He went 65 yards for a touchdown and from then on everybody on the team was crazy about him." The Cards signed him to contract for $5,000.

During his 3-year stint with the Cards, Cross was widely regarded as one of the best blocking backs in the NFL. Both Len Ford of the Browns and Ed Sprinkle of the Bears called him the best blocker of all the backs in the league High praise for the little man. One time Cross blocked the 250-pound Ford so effectively that the Hall of Fame end took a tumble in a surprising flip. Ford exacted revenge the next time the little guy tried to take him with a crackback block. Cross said, "The next time I tried, he flicked his arm. I rolled 10 yards. He came over and helped me up."

In his rookie year, Cross shared the scoring lead on the club with Don Paul. He ran the ball 53 times for a 5.3 average and caught 18 passes for 322 yards while racking up 6 touchdowns. In the first Card-Bear tilt in Comiskey Park in 1951, the unheralded little speedster quickly captured the notice of Chicago fans. He figured prominantly in the Cards upset victory by scoring two TDs. The first came when Frank Tripucka rifled an 18-yard scoring pass to Cross and he followed that up seven minutes later with a 39-yard scoring romp. He was selected as the Cards' MVP of that game and was awarded a tailor-made suit.

Cross joked, "Maybe they selected me because they could have a suit made for me at one-third the price of outfitting some other guy.” In another game in his rookie year, he snared a pass and went 80 yards for a score against the Rams.

Coach Curly Lambeau called him the "most surprising football player he ever coached. He attested, "I found out early that he was tough He proved to me he could do everything just as well, or better, than players of normal size He just runs past, or under, the big fellows." Although the undersized gamer was far from fragile, he had to learn how to take his licks. He didn't always roll "under the big fellows." Cross said, "I learned a lot about how to protect myself. You've got to know how to relax and roll with the tackle." The game little guy almost made it sound easy.

For Hall of Fame quarterback Charlie Trippi, size was not an issue in his assessment of the little blocking back. Trippi was unstinting in his praise, "Pound for pound he's the greatest football player I ever saw."

The general consensus is that NFL players have increasingly become bigger, stronger, and faster. Nevertheless, a look at the height and weight of those who have played in the league in the last ten years demonstrates that there is still a place for the smaller player. It's evident that other factors come into play in making it as a pro. Single-minded determination and desire undoubtedly supersede every other attribute. Those are the qualities that fueled Jack Shapiro and Billy Cross.