Dick Bussell, Buffalo Hunter

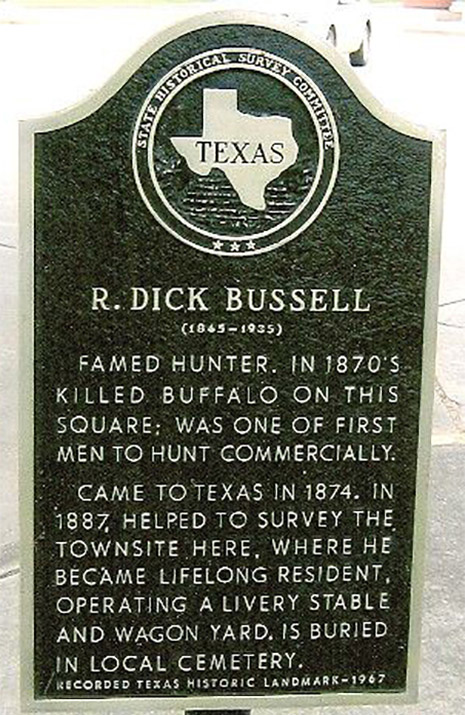

The historical marker at the Court House in Canadian, Texas contains the following text about Dick Bussell:

(1845-1935) Famed hunter, in 1870s killed buffalo on this square; was one of the first men to hunt commercially. Came to Texas in 1874. In 1887, helped to survey the town site here, where he became lifelong resident, operating a livery stable and wagon yard. Is buried in local cemetery.

Dick Bussell, Famed Buffalo Hunter & Pioneer, Historical Marker at the Court House in Canadian, TexasThe following story appeared in the Amarillo Globe News on November 14 1965. It is from an undated story "60-year-old Memories of Panhandle Told by Old Buffalo Hunter," WPA Federal Writers Project Collection, 1936; "The Border and the Buffalo," by John R. Cook.

A hunting outfit consisted of six men," longtime hunter "Uncle" Dick Bussell told Lula Mae Farley in an interview on his 90th birthday. "The owner of the outfit did the killing. There were four skinners and a combination cook and camp rustler, and a guard.

"Each outfit had two wagons. The hunter went out in the morning and made his kill. Then, the wagons came out with the skinners. They had two Spencer carbines with eight cartridges in the magazine, which were used to protect against the Indians. Sometimes, a hunter would kill as many as 100 buffalo at one stand." Once the buffalo were down, the skinners went to work while the hunter let his rifle cool and reloaded ammunition. According to Bussell, each shell was reloaded and fired about 50 times.

"The implements for skinning were three skinning knives, two rippers and a prod stick. The ripper was a straight-blade knife, and the blade of the skinner was turned backwards," Bussell continued. "A grindstone was always at hand to keep the knives at the proper degree of sharpness. The prod stick was about three feet long. A nail was driven in one end and filed sharp, and the other end of the stick was sharpened. The nail was stuck in the flesh of the animal and the other in the ground to hold the hide away from the animal while it was being skinned."

After the morning kill, the shooter returned to camp to melt lead and reload his brass casings while the skinners stripped the hides from the downed animals and pegged them out to dry. Apprentice skinners worked without wage until they became proficient enough to keep up with the more experienced knifemen.

Cookie was not idle between meals. While the beans simmered, he moved among the slain animals, removing tongues to be dried alongside the hides. Dried buffalo tongues were always in demand south of the border and were sold for hard cash to itinerant traders who resold them for a peso each in Old Mexico.

The guard of the buffalo hunting outfit did the least physical work but had the most responsibility of all. Qualifications for a guard included keen eyesight and proficiency with weapons. The guard patrolled the hunting area, ever alert for Indian signs.

"No one ever complained when the guard or scout took his share," former buffalo hunter Alan Weatherton told Works Progress Administration interviewer Constance Marbright in 1938. "More than once, the camp guard made sure all of us came home with our hair still on."

Few hunters hauled their own hides. Enterprising freighters traveled back and forth from the killing grounds, transporting huge stacks of half-dried hides to the nearest railhead for shipment to tanneries back east. Prices ranged from $6 to $10 per hide, and the "assembly line" methods of the hunters could produce as many as 3,000 per month.

Dick Bussell’s 50 caliber buffalo gun is among the treasures on display at the River Valley Pioneer Museum.